Currently Empty: $0.00

The Plague Doctors: Masked Healers of Death

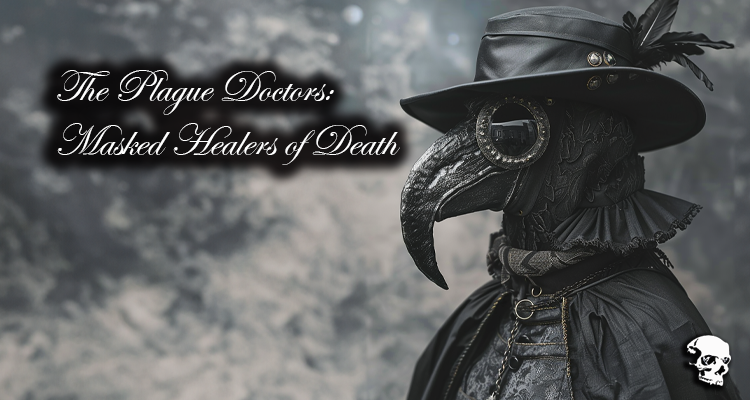

The eerie image of a plague doctor, cloaked in black with a long-beaked mask, has become an iconic symbol of death and disease. These enigmatic figures emerged during the bubonic plague epidemics in Europe, their distinctive attire intended to protect them from the contagion they fought. Yet, their presence was more than just a medical response; it was a psychological and cultural phenomenon that left a lasting impact on the communities they served and on the fabric of history itself.

Origins and Role of Plague Doctors

The first documented outbreak of the bubonic plague, known as the Black Death, ravaged Europe in the mid-14th century, killing an estimated 25 million people—nearly a third of the continent’s population. With little understanding of the disease’s transmission, early attempts to control it were desperate and often misguided. It was during subsequent outbreaks, particularly in the 17th century, that the figure of the plague doctor came into more defined existence.

Plague doctors were typically appointed by cities or towns afflicted by the plague. They were often not experienced physicians but rather individuals who were willing to take on the role for the promise of high pay or the opportunity to gain medical knowledge. Their primary duties included treating plague victims, recording the number of deaths, and conducting autopsies to understand the disease better. However, the effectiveness of their treatments was limited by the contemporary medical knowledge and practices, which were steeped in superstition and based on the humoral theory of medicine.

The Iconic Beaked Mask

The most striking feature of the plague doctor was their beaked mask. This mask, designed by Charles de Lorme, the chief physician to King Louis XIII of France, was an early form of personal protective equipment. The long beak was filled with aromatic substances such as dried flowers, herbs, spices, and a vinegar-soaked sponge. The belief was that these substances would counteract the “miasma” or bad air, which was thought to be the primary means of transmitting the plague.

The mask also had glass eye openings and a long coat made of waxed fabric or leather, gloves, and a wide-brimmed hat. The entire ensemble was intended to create a barrier between the doctor and the disease, though we now know it would have done little to stop the spread of the bacteria Yersinia pestis, which caused the plague. Nevertheless, this eerie costume became a symbol of both hope and terror for the communities it appeared in.

Medical Practices and Superstitions

Plague doctors employed a variety of treatments, many of which were based on the humoral theory that aimed to balance the body’s four humors: blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile. Common practices included bloodletting, the application of leeches, and the use of poultices and potions. Some doctors even resorted to more extreme measures, such as lancing buboes (the swollen lymph nodes characteristic of the plague) or using hot irons to cauterize wounds.

These methods were largely ineffective and often harmful, but they were all that was available in an era when the cause of infectious diseases was not understood. The reliance on such treatments was a reflection of the broader medical and scientific limitations of the time. Despite their dubious effectiveness, the efforts of plague doctors represented a significant attempt at organized public health intervention.

Psychological and Social Impact

The presence of plague doctors had a profound psychological impact on the communities they served. On one hand, their arrival could be seen as a sign of hope—a signal that efforts were being made to combat the disease. On the other hand, their ominous appearance and the association with death and suffering often exacerbated the fear and hysteria surrounding the plague.

The beaked mask, in particular, became a source of fascination and terror. Its bird-like appearance was often interpreted as a harbinger of death, echoing medieval superstitions about birds as omens. This association was reinforced by the doctors’ role in recording deaths and performing autopsies, tasks that kept them constantly in close proximity to the deceased.

Cultural and Artistic Legacy

The image of the plague doctor has endured in cultural memory, often symbolizing the struggle against unseen and deadly forces. In literature and art, plague doctors have been depicted in various ways, from the sinister to the heroic. The mask, with its hauntingly long beak, has been a particularly potent symbol, appearing in everything from paintings and engravings to modern-day Halloween costumes and horror films.

One of the most famous literary depictions is found in Daniel Defoe’s “A Journal of the Plague Year,” which provides a detailed, albeit fictionalized, account of the Great Plague of London in 1665. Defoe describes the efforts of medical practitioners and the pervasive fear that gripped the city. The plague doctor, in his dark robes and mask, stands as a figure of both bravery and morbidity.

In visual art, the plague doctor has been a subject of fascination for centuries. Paintings and drawings from the Renaissance and Baroque periods often depict them tending to the sick or walking through deserted streets, a grim reminder of the epidemics that devastated Europe. More recently, the image has been appropriated in various forms of media to evoke themes of death, disease, and the fragility of human life.

Evolution of Public Health

While the practices of plague doctors may seem primitive and misguided by today’s standards, they represent an early form of public health response to infectious disease outbreaks. The appointment of plague doctors was an attempt to systematize and professionalize the care of the sick, a step towards the more organized and scientific approaches that would develop in later centuries.

The bubonic plague outbreaks highlighted the need for better medical knowledge and public health infrastructure. Over time, these lessons contributed to significant advancements in medical science and the development of practices such as quarantine, sanitation, and vaccination. The experiences of the plague doctors, with their mix of bravery and futility, underscore the importance of continuous learning and adaptation in the face of public health crises.

The plague doctors of the bubonic plague era remain one of history’s most fascinating and unsettling figures. Their distinctive beaked masks and dark robes have become symbols of a time when death was omnipresent, and medical knowledge was still in its infancy. Despite their often gruesome and ineffective methods, these masked healers represented a crucial attempt to combat one of humanity’s most devastating diseases.

Their legacy lives on, not only in the annals of medical history but also in the cultural and artistic expressions that continue to evoke the haunting image of the plague doctor. As we look back on their contributions and limitations, we are reminded of the importance of scientific progress and the enduring human desire to understand and overcome the forces of disease and death.

Are you enjoying this article or our site? Love of Gothic and the Dark Matters & Mischief magazine are run by dedicated volunteers, and we rely on crowdfunding to cover our expenses. Your support is crucial to keep us going! Consider becoming a paying member of our Patreon or purchasing something from our shop to help us continue providing content and community support. Thank you for your support!